It’s Not Your Fault: The Enduring Genius of ‘Good Will Hunting’ and the Battle to Free the Mind From Its Own Prison

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), a fortress of intellectual rigor, is an unlikely setting for a story about emotional redemption. Yet, the 1997 film Good Will Hunting—a script penned by two young unknowns, Matt Damon and Ben Affleck—gave us exactly that: a cinematic masterpiece where complex mathematics was merely the backdrop for a profound, emotionally wrenching journey into the heart of trauma. At its core, the film is not about solving algebraic proofs; it’s about solving the problem of a deeply broken, yet uniquely brilliant, soul.

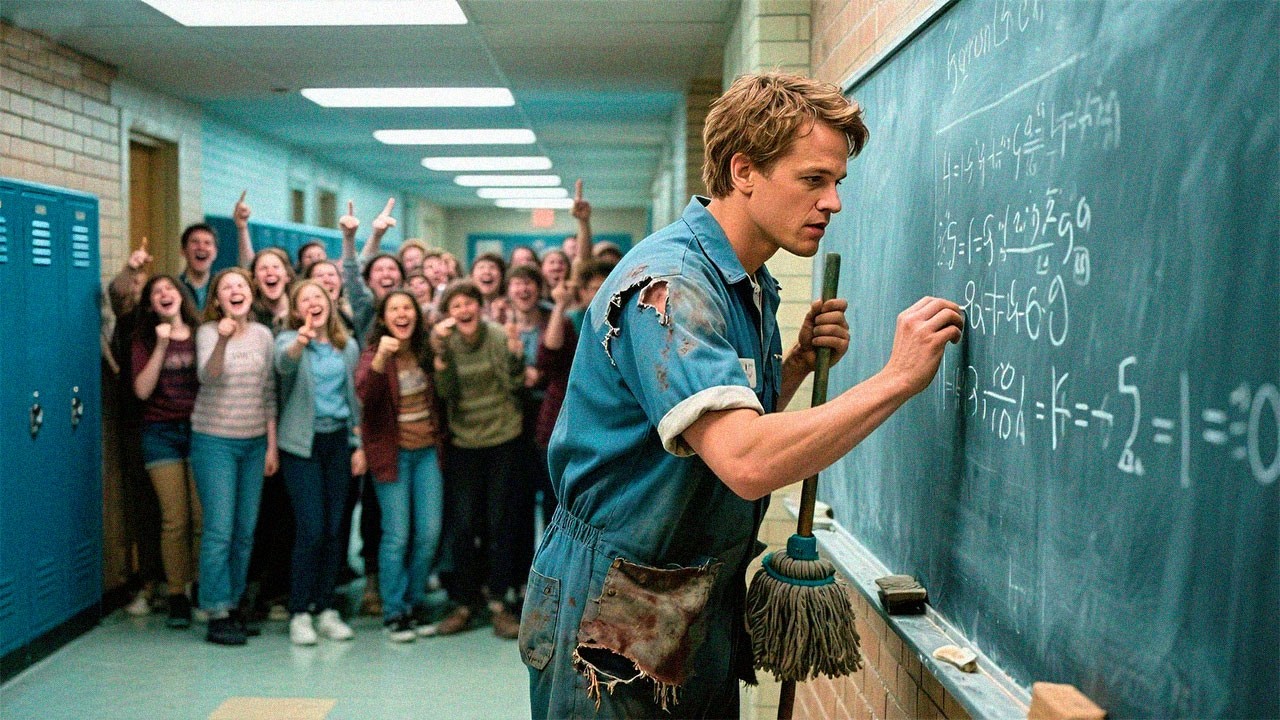

The character of Will Hunting, played by Matt Damon, is instantly iconic. He is a 20-year-old janitor from a rough South Boston neighborhood, an orphan with a history of abuse and juvenile crime. He is also a polymath who can quote Kant, dissect historical figures, and, most famously, anonymously solve a challenging theorem posted by MIT’s Fields Medalist, Professor Gerald Lambeau. Will’s genius is undeniable, but it is also a liability—a sophisticated defense mechanism he uses to push away the world, creating a prison of intellectual superiority that shields him from true connection.

The core narrative tension explodes when Will is arrested after a bar fight. Lambeau, desperate to harness this unparalleled intellectual gift, strikes a deal with the court: Will is released on the condition that he studies math weekly with Lambeau and attends therapy sessions to address his deep-seated criminal tendencies. This arrangement sets the stage for the film’s true confrontation, not in an academic lecture hall, but in the quiet, bruised office of therapist Dr. Sean Maguire, played in an Oscar-winning performance by Robin Williams.

The Two Geniuses: Will vs. Sean

The therapy sessions between Will and Sean are the magnetic center of the film. Lambeau views Will as a scientific resource—a problem to be solved and utilized. Sean, his former college rival and an emotional academic, views Will as a person—a wound to be healed. This contrast forms a critical philosophical debate: Does genius obligate a person to fulfill their intellectual potential, or does it simply grant them the freedom to choose their own life?

Will’s intellectual armor is impenetrable. He reads the first therapist’s book and flawlessly mocks his entire psychological methodology. He quickly dismisses the second therapist with sarcastic remarks. But when he meets Sean, the game changes. Sean, whose own life has been marked by personal pain—the loss of his wife to cancer—refuses to engage on Will’s intellectual terms.

In their pivotal second session, held on a simple park bench, Sean delivers the monologue that defines the film’s emotional thesis. He acknowledges Will’s vast, book-learned knowledge, but points out the emptiness of it:

“You’ve read every book in the library, but you’ve never smelled the air in Paris… You’ve never been in a war… You can quote sonnets about love, but you’ve never looked a woman in the eye and been totally vulnerable… You think I know about your life because I read an official folder? I can’t learn anything from you that I can’t read in some goddamn book.”

This moment is not just a critique; it’s an invitation to vulnerability. Sean strips away Will’s shield of facts and information, forcing him to realize that his brilliance is a sophisticated form of hiding. He is a genius who knows everything about the world except his own pain and his own future.

The Self-Imposed Prison and the Fear of Intimacy

Will’s inability to commit is rooted in a fundamental fear of abandonment, a direct result of the abuse he suffered as an orphan. He sabotages every positive opportunity: he refuses to work with the prestigious scientists Lambeau sets up, and he attempts to push away Skyler, the medical student who genuinely loves him.

His confession about Skyler is heartbreakingly honest: he doesn’t want to ruin the “perfect image” he has of her, which Sean immediately counters as a fear of ruining his own perfect, controlled image. Will keeps Skyler at arm’s length, even lying about his family, because true intimacy means becoming vulnerable enough to be hurt. To love someone is to open himself up to the possibility of the pain he experienced as a child.

Sean’s response to Will’s fear is another moment of profound truth. He shares the tiny, imperfect details of his late wife—her nervous habit of farting in her sleep—revealing that “those are the things I miss the most.” True intimacy, Sean argues, is found not in perfect images, but in accepting the beautiful, messy imperfections of another person. It is the core message that Will’s intellectual knowledge—his “genius”—cannot teach him.

The Power of Choice and the Role of Friendship

The conflict between Lambeau and Sean further clarifies the question of Will’s destiny. Lambeau sees an obligation to a higher intellectual pursuit, driven by a fear that Will will squander his gift by becoming a bricklayer or shepherd. Sean, however, is insistent that Will must choose his own path.

The argument between the two academics is resolved not by another professor, but by Chuckie Sullivan, Will’s lifelong best friend, played by Ben Affleck. Chuckie’s speech to Will—the unschooled laborer telling the certified genius to get out of town—is the film’s most powerful affirmation of friendship and selfless love. Chuckie admits his greatest dream is not to stay with Will, but to show up one morning and find him gone, finally pursuing a life worthy of his talent.

“If you’re still here in twenty years, if you’re still hanging around here, coming over to my house to watch the game… that’s not fair. I mean, you got a responsibility to me… I wanna see you go. I wanna see you get your ticket.”

Chuckie’s willingness to sacrifice their friendship for Will’s freedom provides the final emotional push. It is an act of pure, unconditional love that Will’s abused psyche is finally capable of recognizing.

The Final Breakthrough

In the film’s climatic therapy session, Sean does away with analysis and intellect. He returns to the abuse Will suffered, focusing intensely on the phrase in Will’s file: “It’s not your fault.” Will attempts to brush it off, to intellectually dismiss the words, but Sean simply repeats it, relentlessly, cutting through every layer of sarcasm and self-loathing.

It is the moment the armor fails. Will, who has never cried in his adult life, breaks down, clinging to Sean, finally accepting that the pain and violence he endured was not something he deserved or caused. He is finally ready to let go of the shame and rage that has defined him.

The resolution is perfect in its quiet simplicity. Will turns down the prestigious, golden-cuffed job at the National Security Agency. He does not become the lab rat Lambeau wanted; he does not become the shepherd Sean warned him about. He makes his own choice. He drives off in the car his friends built for him, leaving a note for Sean using the therapist’s own phrase about his late wife: “I had to go see about a girl.”

Good Will Hunting endures because it reminds us that true genius is worthless without emotional courage. The greatest challenge Will Hunting ever faced wasn’t a mathematical proof on a whiteboard, but the emotional truth within himself. The film, and the powerful performance of Robin Williams, serves as a timeless reminder that while knowledge can be learned from a book, the wisdom to truly live must be earned through vulnerability. The final gift Sean Maguire gave Will Hunting wasn’t a career path; it was permission to breathe, to love, and to finally forgive the child he once was.

News

The Landlord of the Lake: How a Lone Cabin Owner Exposed a Massive HOA Racketeering Ring

The Lady in Heels and the $50,000 Insult In the small, mountainside community of High Pines, the arrival of…

From Homeless to Home: How a Single Dad’s Christmas Eve Kindness and a Tattered Cookbook Unmasked a Chef’s Stolen Life

The Christmas Eve Rescue: A Question That Changed Everything The air in Milbrook, Colorado, was thick with the manufactured…

The K9’s Secret: How a Rescue Dog and a Blizzard Unmasked a Corrupt Sheriff and Saved His Late Partner’s Wife

Six Inches of Silence, a Broken Cruiser, and a Growl That Spoke Volumes The early morning hours in Milbrook,…

Maintenance Man, Formerly an Elite Diplomatic Security Instructor, Neutralizes Corporate Thugs with a Cracked Spoon, Exposing the Company Tied to His Wife’s Death

The Invisible Man Who Saw Too Much Evan Hale had perfected the art of invisibility. At 35, he was…

Gavel to Garrote: Judge’s Son Choked in Court, Unmasking a Police Union’s Conspiracy of Silence

A Day of Testimony Becomes a Day of Judgment The atmosphere inside the wood-paneled chamber was already thick with…

The Cinderella of the Pavement: How a Homeless Woman Eclipsed the Royal Wedding of the Year and Challenged the Heart of Privilege

The Cinderella of the Pavement: How a Homeless Woman Eclipsed the Royal Wedding of the Year and Challenged the Heart…

End of content

No more pages to load