No one claimed the bride because she’s old until a little girl pointed, “That’s her. That’s my mama.” Dry Creek 1,889. The noonday sun sat like molten brass over the small train station, throwing hard light across the dusty boards and iron rails.

Dust swirled with every gust of wind, turning the air into a haze of ochre and grit. Wooden wagons creaked, horses stamped and snorted. The people of Dry Creek had gathered, shopkeepers in rolled up sleeves, ranch hands smelling of leather and sweat, women in faded bonnets clutching children’s hands. They were waiting for the mail order brides. These women, whispered about for weeks in the saloon and the merkantile store, had answered printed advertisements sent out by lonely men in the West. They came from as far as Boston and Baltimore. carrying trunks and dreams, hoping to step off a train

and into a husband’s arms. Dry Creek had not seen such a spectacle in years, and the town’s folk buzzed with anticipation like bees around a hive. The whistle sounded long and low. A black locomotive emerged from the heat shimmer, churning steam and smoke into the sky.

Brakes squealled, metal clanged, and the train lurched to a stop. The crowd pressed closer. Children craned their necks. Men adjusted their hats. Three young women stepped down first. One with hair the color of corn silk was immediately claimed by a freckled rancher. Another, small and dark-haired, ran into the arms of a grinning man with a new suit.

The third, cheeks flushed pink from travel, was swept into a hug by a bearded homesteader who lifted her trunk with ease. Cheers and claps rose. The station platform smelled of perfume and coal smoke. Then came another figure. She was about 30, though the sun and years had carved faint lines at the edges of her eyes. Her dress was simple.

A gray calico neatly pressed but plain. A worn carpet bag hung from one hand. In the other, she clutched a folded letter. Her brown hair was pinned tightly beneath a modest hat. She stepped down slowly, scanning the crowd. Her eyes, a deep and tired blue, searched for someone who did not appear. No man stepped forward.

She stood alone on the platform as the last passengers disembarked. The conductor shouted something to the porter, swung aboard, and with a hiss of steam, the train began to pull away. Wheels clattered, and the long cars rolled down the track, shrinking into the bright horizon. Dust rose where it had stood, then settled again. The crowd, still lingering, shifted its gaze to her. Whispers rustled through the onlookers like dry grass in wind.

“She’s too old,” a woman murmured behind a gloved hand. “Who’d want a widow that age?” a man muttered near the hitching post. “Betty changed his mind,” another voice snickered. She heard them. Her fingers tightened around the letter until the paper creased. It was a promise written in a stranger’s hand. words of a man named Thomas Reed, who had asked her to come west and marry him.

She had read it so many times on the journey that she knew every stroke of ink. Yet now the platform was empty, but for her and her trunk, her cheeks flushed, though not from the Sunday. She straightened her back and tried to steady her breath. The dust made her eyes sting, but she would not let the tears fall.

The town’s folk began to drift away, some shaking their heads, others smirking. A wagon rolled off, its wheels crunching gravel. A man spat tobacco and turned toward the saloon. The air felt heavier with every second she stood there, alone, exposed, unchosen. Then, from the far edge of the platform, a small figure appeared. A girl of about six, hair the color of wheat, in a patched gingham dress, holding a ragd doll by its limp arm.

She had been skipping along the wooden boards, chasing the patterns of sunlight between the slats. She slowed when she saw the woman. The girl’s wide eyes fixed on her face. She tilted her head as if comparing a memory to the living person before her. The ragd doll swung back and forth.

The woman managed a faint, uncertain smile. Something in the child’s gaze pierced her, an odd mixture of recognition and hope. The girl took a hesitant step closer. She looked over her shoulder, then back at the woman. Her small chest rose and fell quickly as if she had run a long way. She opened her mouth, closed it, then opened it again.

“That’s her,” the little girl said, voice clear and high. She pointed a small finger straight at the woman. “That’s my mama.” The platform went silent. Boots stopped moving. A woman dropped her parasol and it clattered on the wood. A horse snorted and pawed the ground. The gossip died in mid-breath. Every eye turned to the girl and the stranger, she claimed.

Even the wind seemed to pause, holding the dust in the air. The woman’s heart slammed against her ribs. She stared at the child, frozen, the letter still crumpled in her fist. She did not know her, had never seen her before. Yet in that instant something flickered across her face, shock, confusion, and something softer, like the faint echo of a forgotten dream.

And the crowd, which had been so loud with judgment moments before, now stood utterly still, caught between disbelief and wonder. Her name was Margaret Callahan, though most folks who came to know her called her Maggie. Before the war, she had been a school teacher.

During it, she had stitched wounds and held the hands of dying boys in field tents that smelled of blood and smoke. Afterward, she had buried a husband who never truly came home from the battlefields of Tennessee, even though his body had, and now she stood in Dry Creek, neither wife nor widow in anyone’s eyes, just a woman alone in a land that offered no mercy for such things. The little girl still held her hand. Maggie looked down at her and managed.

Sweetheart, I think you’ve mistaken me for someone else, but the girl shook her head stubbornly. No, I saw you in my dream. You came on a train just like now, and you smiled just like that. Maggie wasn’t smiling. Not really. She looked up to see a few towns folks still watching her. Their curiosity mingled now with something else. discomfort perhaps. One woman pulled her child away.

A man with a mustache mumbled something under his breath and stroed off. From the corner of her eye, Maggie spotted the hotel across the street, a modest two-story building with lace curtains and a sign that read, “Dry Creek Boarding House and T-room.

” With as much dignity as she could summon, Maggie gathered her bag and walked toward it, the little girl trotting beside her. Inside the lobby smelled faintly of lemon polish and dust. A desk clerk looked up from his ledger as Maggie approached. “I’d like a room, please,” she said. He looked her over slowly, then glanced toward the girl. “Where’s your husband?” “I He’s been delayed,” Maggie replied, trying to keep her voice steady. The clerk frowned.

Ma’am, this establishment does not rent to unaccompanied women unless they have a letter of character or a male reference in town. I have a letter, she said quickly, pulling the folded parchment from her pocket. From Thomas Reed. He’s the man who sent for me. The clerk took it, scanned the first few lines, and handed it back with a shrug.

If he doesn’t come claim you, it’s no good to me. I’ve got rules. Maggie stood still, her throat tight. I have nowhere else to go. There’s the church. Or maybe someone will take pity, but I’ve got paying customers. Good day to you, miss. He turned away before she could answer. Outside, the wind had picked up again, carrying grit against her cheeks.

She stood on the wooden sidewalk, trying to think. She could not go back east. Her money had gone into the train fair. every last coin saved from years of sewing, cleaning, and hope. She had wagered everything on a stranger’s promise, and he had not come. The girl beside her tugged at her sleeve. “You can come home with me,” she said simply.

“We have biscuits, and I have a doll that smells like cinnamon.” Maggie’s heart gave a painful twist. “What’s your name, darling?” she asked. “Ellie,” the girl replied proudly. Ellie Cain. Well, Ellie Cain, Maggie said gently, kneeling to her level. I think your mama and papa might be worried if you keep running off. I don’t have a mama, Ellie said matterofactly.

She went to heaven when I was three. Papa says that means she watches from the stars, but I don’t think she came back. I think I think maybe she became someone else. Maggie stared at her. She should have corrected the child. should have walked away, found the sheriff or the church, or anywhere but here. But Ellie’s small hand found hers again, warm and certain.

And Maggie, who had been no one’s daughter, no one’s wife, and no one’s future for so long, let herself hold on. The sound of boots striking the boardwalk came fast and firm. Ellie. The little girl froze. Maggie turned to see a tall man striding toward them from the direction of the blacksmiths, broad-shouldered, sunworn, with a beard that shadowed his jaw and eyes the color of storm clouds.

He wore a simple work shirt, sleeves rolled to the forearms, and a carpenters’s apron still dusted with sawdust. He stopped short when he saw them together. “Papa,” Ellie chirped. “Get away from her,” the man said, his voice low, but sharp as a knife. You do not run off like that. Ellie clutched Maggie’s hand tighter. She’s not a stranger. She’s my mama.

Jonah Kane blinked, his mouth opened slightly, then closed again. He looked at Maggie, really looked at her for the first time. Maggie felt her cheeks heat under his gaze, not from attraction, but from pure mortification. She stood upright and stepped back. I I assure you, sir, I didn’t. She just she followed me. Ellie cut in.

She didn’t do anything wrong. I found her. Jonah crouched and took Ellie gently by the shoulders. Sweetheart, you know better than this. You do not wander off with people you don’t know. But I do know her. Ellie insisted, voice rising. I saw her in my dream. She came on the train. She looked at me just like this.

Jonah stood exhaling through his nose. He looked to the town’s people. Some had lingered watching. A few laughed under their breath. One man said, “Looks like the girls got more sense than her old man.” Maggie stiffened, embarrassed. “This is clearly a misunderstanding. I’ll find my way.” She turned, but Ellie’s small cry stopped her.

“Please don’t go. She’s supposed to be here, Papa. I prayed for her.” Jonah hesitated. Rainclouds had begun to gather over the hills, casting shadows over the street. The wind carried the scent of thunder. He looked again at Maggie, tired, alone. Her dress travel wrinkled, a letter still folded in her hand. The girl clung to her like she belonged there.

He ran a hand down his beard, sighed, and said, “Where are you staying?” “I I have nowhere,” Maggie admitted. “The boarding house refused me.” He nodded slowly, jaw clenched. Then he said, “It’s going to rain soon. You can come to our place.” “One night.” Maggie’s lips parted. “That’s not necessary.” “I did not say it was,” Jonah said, already turning. “But I’m not letting my daughter walk home in a storm.

” Ellie beamed and took Maggie’s hand again, skipping beside her as Jonah walked ahead. Their home sat a quarter mile out past the edge of town. It was modest but well-kept. A wooden cottage with smoke curling from the chimney and rows of chopped wood stacked neatly beside the porch. Chickens scratched near a shed.

A wagon sat under an awning. Inside it smelled of pine and sawdust. The furniture was sturdy handmade. There were few decorations, just a faded photograph on the mantle, a pair of sewing shears hung on the wall, and a worn quilt folded at the foot of the couch. Jonah lit a lamp without a word, gestured to the chair. “Sit. I’ll bring a basin.

” Maggie sat, stiff as a plank. Ellie pulled her doll from a shelf and plopped down on the rug. This is Betsy. She’s had a hard year, too. Jonah returned with a basin and cloth. You can wash up in the kitchen. Thank you, Maggie said softly. He nodded once, then returned to the far side of the room, taking out a small piece of wood and his carving knife.

He did not speak again. That night, after supper, Ellie fell asleep on Maggie’s lap. Jonah looked up from his corner. The lamp light cast warm gold across his face, softening it. He didn’t smile, but something in his expression had shifted. “Less stone, more earth. You can take the cot in Ellie’s room,” he said. “Just for tonight.

” Maggie looked down at the sleeping child, then up at the quiet man who had said so little and done so much. “All right,” she whispered. The room Jonah gave her was small, just wide enough for a cot, a wash stand, and a narrow window that looked out on the barn, but it was clean, and the blanket smelled faintly of cedar.

Maggie kept her carpet bag packed at the foot of the bed, ready to leave the moment she found work. She would not overstay her welcome. But the days passed, and no work came, the dress maker already had an assistant. The school teacher post was filled. The saloon offered her a job pouring whiskey, but Jonah shook his head so firmly when he overheard the offer that Maggie politely declined before she even considered it.

So, she stayed temporarily. She swept the floors, patched Ellie’s dresses, and taught the girl to read from an old Bible left on the shelf. She baked biscuits from scratch, even though the flower was coarse and the lard was near rancid. She fixed the hinge on the back door and mended Jonah’s work shirt when it tore at the elbow. She never asked for thanks. She simply did.

And something shifted. The house, once silent, but for the crack of firewood and the scratch of carving knives, now carried the sounds of laughter, soft, spontaneous. As Ellie chased chickens in the yard or danced in the kitchen while Maggie stirred stew, the air inside felt warmer somehow lived in. Jonah noticed.

He never said anything, but Maggie caught him watching sometimes over the rim of his coffee cup or from the workbench out back. His eyes weren’t suspicious or possessive. They were curious, quietly stunned, as if he could not quite believe the presence of her had changed the house without her trying. But the town noticed too.

At the merkantile, a woman named Mrs. Albbright leaned in too close as Maggie examined a spool of thread. You know, she whispered, “Some folks say Jonah Kane’s harboring another man’s bride. Shameful, really, and with a child in the house.” Maggie froze.

She smiled politely, set the thread back on the shelf, and walked out with her chin high. That night, she said nothing. But when Jonah found the shirt she had mended folded on his chair, there was no note attached, just thread, clean and strong. A week passed, then another. One night, as the wind howled over the plains, and the shutters rattled softly against the windows, Maggie sat by the hearth while Jonah cleaned his tools.

Ellie was already asleep. The fire was dying. She stood quietly, smoothed the front of her dress, and stepped toward the door. Jonah looked up. “I want to thank you,” she said, not meeting his eyes. “For letting me stay, but I think it’s time I moved on. I will find a way to earn my keep elsewhere.

” “He said nothing for a long moment.” The silence stretched like taut rope between them. Then he set his tools down carefully and stood. When she reached for the latch, she saw him already there standing on the front porch, arms folded, the wind tugging at his sleeves. Where will you go? He asked. I’ll find a way, she replied. You said that two weeks ago.

I meant it then, too. I meant it then, too. I meant it then. He stepped forward just enough that the fire light touched the edge of his profile. He looked like a statue carved from old wood and memory. “If you leave,” he said quietly, “he will dream again.” Maggie blinked. “Dream,” she told me. “The night you arrived, she said you came from her dreams.

Said you were her mother. You saw how hard she held on to that.” Maggie looked down. Jonah continued, his voice a low rumble. If you walk away now, she’ll wake up every night waiting for someone who never came like her real mother did. I won’t put her through that again. I’m not her mother,” Maggie whispered. “No,” he agreed.

“But you’re the only woman who’s ever looked at her like she mattered.” A gust of wind swept through, curling dust around their feet. Maggie stepped back from the door. Inside, Ellie stirred in her sleep and murmured something too soft to hear. Jonah turned and walked back into the house without another word. Maggie followed.

The first time Jonah heard the name Thomas Reed spoken aloud in Dry Creek, it came from the lips of the blacksmith’s boy. “He rode in from the south trail,” the boy said breathless. “Said he’s here looking for a drink and maybe some fun.” Jonah didn’t react. Not right away. He just tightened the bolt he was fitting into a fence post and stood up slowly.

Maggie was in the garden coaxing life out of dry soil. Ellie was chasing a butterfly near the chicken coupe, giggling. Jonah wiped his hands on a rag and walked toward town. The saloon was half full, the usual haze of smoke and sweat hanging thick in the air. Laughter spilled from the open doors. Inside, at the far end of the bar, a man with sllicked hair and a crooked smile nursed a whiskey and bragged to anyone who would listen. I sent a letter.

Sure, Thomas Reed was saying, told her I’d marry her, bring her west. Figured I’d get a look and see if she was worth the trouble. He chuckled and tossed back another drink. But she looked older than I thought, worn out. I never planned to show. A few men laughed nervously. Others shifted uncomfortably. Jonah stepped inside slow and steady. Thomas turned when he felt the weight of his stare.

“You the sheriff?” he asked, smirking. I didn’t break no law. Just made a lady dream a little. Jonah didn’t speak right away. He walked across the creaking floorboards and stopped just a few feet from him. “You left her on the platform like a sack of mail,” Jonah said, voice low. “And now you’re here laughing about it.” “Thomas” shrugged.

“Hell, I didn’t force her to come. It was just a letter. She gave up everything,” Jonah said. “She believed you.” Thomas narrowed his eyes, sensing a shift in the air. What’s it to you anyway? Jonah’s hands stayed at his sides. He didn’t reach for his belt, didn’t ball his fists.

He just stood tall, quiet, and unmoving like a storm before the lightning. “It’s this,” he said finally. “She’s not your bride. She never was.” Thomas raised an eyebrow. “That’s so. That’s so,” Jonah replied. “Because Maggie Callahan is not waiting to be claimed. She’s already family. The saloon went dead quiet. One man lowered his glass.

Another removed his hat as if out of instinct. Even the piano player, halfway through a tune, let the keys go silent. Thomas laughed once, incredulous. You married her? No. Jonah said, “But my daughter calls her mama, and I reckon that means more than any letter you ever wrote.” Thomas stood trying to puff himself up, but his boots didn’t quite meet Jonah’s height.

Easy to play hero with a housekeeper, he spat. Jonah didn’t blink. She’s not a housekeeper. She’s the reason my little girl sleeps through the night. She’s the reason there’s warmth in a home that’s been cold for too damn long. He leaned in just enough for the other man to feel the weight behind the words. You came here to brag, Jonah said.

Now ride out because if I hear you so much as breathe her name again, you’ll find out how quiet a carpenter can be when he’s burying something he doesn’t want found.” Thomas backed down. He scoffed, tossed a few coins on the bar, and stroed out with false bravado, but no one followed. No one laughed. When the doors swung shut behind him, the room stayed hushed.

Jonah looked around once, then he turned and walked back out into the street. No fanfare, no applause, just the simple weight of a man who said exactly what needed saying. Maggie never asked what happened that afternoon. But when Jonah came home, he set his hat on the peg and reached for the spoon she was stirring soup with.

“I’ll finish that,” he said. Their hands brushed, and neither pulled away. Dry Creek had seen droughts, fires, and blizzards, but nothing spread faster than fear. It began with a cough. a child, then two, then five. Within days, the fever had taken hold of nearly every young one in town. Mothers wept at bedside.

Fathers rode out in desperation, searching for doctors who never arrived. The local physician had fled by the third night, packing his bags and leaving a note that simply read, “By my skill. Pray. Pray.” Maggie did not pray. She worked. Her hands, trained by war, moved with calm precision.

She boiled linens, mixed tinctures from what herbs she could find, rationed willow bark tea for the worst of the fevers. She moved from house to house, checking pulses, wiping brows, giving what comfort she could. Jonah stayed beside her, not a healer, but a steady presence. He carried water, split wood for fire, helped grind roots into paste. Word spread fast. The woman some had mocked as unwanted was saving their children. But then Ellie fell ill.

It started with a shiver at supper. A pale flush crept across her cheeks. By morning, she was too weak to lift her doll. Maggie didn’t wait. She stripped the girl’s bedding, boiled every cloth in the house, and made a small cot beside the fireplace where she could keep her close. Jonah hovered nearby, helpless in a way that broke him open.

His daughter, once full of sunshine, now lay limp in the crook of Maggie’s arm, her breath shallow. I need more bark, Maggie said, not looking up. And water clean from the spring. Jonah nodded and disappeared into the wind. Maggie sat by the fire, wiping Ellie’s face again and again. She whispered stories into her ear.

Tales of fields of daisies, of horses with wings, of mothers who never left. Ellie moaned softly, her lips cracked, her eyes barely opened. “Mama,” she breathed. “Don’t let me die.” The words sliced through Maggie like a blade. “I’m here,” she whispered, voice steady, but her soul trembling. “I’m right here, baby. You hold on.

” Jonah returned with bark and water and dirt under his nails. He found Maggie still bent over the girl, her own hair falling loose around her face. They worked together into the night, boiling, cooling, wrapping, praying without saying so. As the fire dwindled, Jonah settled into the floor beside Ellie’s cot. He took her small burning hand in his.

“She’s strong,” he murmured more to himself than to Maggie. “She’s always been strong.” “She gets that from you,” Maggie said, crouching beside him. He didn’t answer. Just kept holding his daughter’s hand like it was the last real thing left in the world. Maggie reached out and placed her palm on Jonah’s shoulder. For a moment, he didn’t move.

Then he leaned into her touch just slightly, but enough. No words passed between them, nothing needed to. Because in that stillness, in the hush of fire light and fevered breathing, a bond was forged, raw and real and silent. A man who had closed every door since grief found himself leaning on someone he hadn’t asked for. A woman who had long since stopped hoping found herself anchored beside a man who never said the things she longed to hear, but did them instead. They kept vigil as dawn approached.

And when Ellie stirred just before the sky turned pink and whispered, “Mama,” with breath that no longer trembled, Maggie cried for the first time in years, quietly into her own sleeve where no one could see. But Jonah saw, and he reached for her hand, this time not out of necessity, but choice.

The fever passed like a storm, leaving behind silence, relief, and the lingering scent of boiled herbs. Children who had once burned with sickness now ran barefoot through the streets again. Mothers wept openly in church pews. Fathers nodded at Maggie in the street, their eyes fuller than any words could say. No one in Dry Creek looked at her the same anymore. She was no longer the mail order bride who got stood up.

She was Miss Maggie, the one who stayed when others fled, the one who held their babies through nights of fire. A week after the last child recovered, the town’s folk gathered at the chapel for a potluck supper in her honor. They brought stews and cornbread, venison pies, and jars of sweet pickled beets.

Maggie, uncomfortable with the attention, stood near the back, smiling politely as people approached with words of thanks and offers of fresh eggs, new dresses, even a cow. She accepted nothing but their gratitude. Jonah wasn’t there. Not at first, but later, as twilight thickened over the horizon and lanterns were lit, he appeared at the chapel door, freshly shaved, boots clean, a plain wooden box in his hand.

Maggie noticed him immediately, not because he entered with any flourish, but because the quiet around him deepened as he moved. Ellie rushed to his side, tugging at his coat. “Did you bring it?” she whispered loudly. He nodded once and handed her the box. Maggie’s brow furrowed as Ellie trotted over, grinning ear to ear. “Open it,” the girl said, breathless with excitement.

Inside was a ring, simple, imperfect, forged from silver scraps and worn smooth at the edges. It wasn’t polished. It didn’t shine, but it was unmistakably made by hand. Maggie looked up to find Jonah standing beside her now, hat in hand. I melted down my mother’s spoon, he said quietly. Took me a week to shape it.

She opened her mouth, but he lifted a hand soft, steady. I’m not good with speeches, he said. Never was, and I didn’t write you letters. Maggie’s throat tightened. I didn’t send for you, he continued. But you came and you turned this house into a home. Turned my daughter’s dreams into mournings. turned my silence into something that doesn’t feel empty.

The lantern flickered nearby, casting gold across his face. I don’t need a preacher’s blessing or a certificate. I just need you to say yes. He didn’t kneel. He didn’t ask. He just stood there solid, honest, offering everything in the way only a man like him could. Maggie stared at the ring, then at his hands, then at Ellie, who watched them both with a look of pure hope, and finally she looked at Jonah, the man who had never promised her anything, but gave her everything real.

Her voice was barely a whisper. “Yes!” Jonah nodded once, then gently slid the ring onto her finger. It didn’t sparkle, but it fit. The wedding was small. No organ, no pews, no lacecovered aisle, just a patch of open prairie behind Jonah’s home, where the tall grass swayed in time with the breeze and the sky stretched wide like forever.

Maggie wore a dress she had sewn herself, ivory cotton with a row of mother of pearl buttons she had found in a forgotten drawer. Her hair was pinned back with care, and Ellie had tucked a wild flower behind her ear just before the ceremony began. Jonah wore his cleanest shirt and boots, newly polished with bacon fat.

He did not speak much that morning, but when he looked at her, Maggie felt steadier than any altar could provide. Ellie stood between them, barefoot in a soft blue dress, clutching a bundle of daisies and golden rod she had picked herself. She beamed up at Maggie like the sun had settled in her chest.

The town’s folk gathered around, quiet with respect. These were the same people who once pied her on the platform. Now they smiled at her like she belonged. The pastor kept it brief. Vows were exchanged not with flowery promises but with hands held tight and eyes that said everything. Afterward there was pie and lemonade.

Laughter, a fiddle tune played by the blacksmith’s brother. Children ran wild through the grass while the wind carried the scent of honeysuckle. As twilight settled over the hills, Maggie sat beneath the oak tree with a folded letter in her lap, parchment worn soft at the edges, written not in ink, but in the silence of her thoughts. She read the words aloud, though no one else could hear them.

Dear Mama, you always said love would come when I least expected it. I never expected it at all. Not when I stepped off that train. Not when I stood alone with nothing but dust on my hem and shame in my chest. No one claimed me that day. I wasn’t young enough. I wasn’t soft enough. I wasn’t anyone’s dream.

But one little girl reached out her hand. And one quiet man stood by me when I tried to walk away. I wasn’t chosen when I arrived. But in the end, someone looked at me like I was the thing he’d been waiting for his whole life. And now I’m home. She folded the letter slowly, pressed it to her chest, and let out a breath that felt like laying down an old burden. Jonah stood nearby talking to the pastor.

Ellie was chasing fireflies, and Maggie Callahan, once unwanted, now wholly known, smiled into the soft dusk, the ring on her finger warm from the Sunday. Thank you for watching this unforgettable tale of love found in the unlikeliest of places. If this story stirred something in your heart, if you believe that love can still rise from dust, from silence, from the edge of goodbye, then don’t forget to hit that like button and tap subscribe to join us on Wild West Love Stories.

Every week, we bring you handcrafted romance set in the untamed heart of the American frontier, where bullets missed but hearts didn’t. Turn on notifications so you never miss a love story that lingers long after the credits roll. This is Wild West Love Stories where legends loved and love became legend.

News

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009”

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009” After over a decade of whispers,…

The Unseen Battle of Matt Brown: The Dark Truth Behind His Disappearance from ‘Alaskan Bush People’

For years, the Brown family, stars of the hit reality series “Alaskan Bush People,” captivated audiences with their seemingly idyllic…

From “Mr. Fixit” to Broken Man: The Unseen Tragedy of Alaskan Bush People’s Noah Brown

Noah Brown, known to millions of fans as the quirky, inventive “Mr. Fixit” of the hit Discovery Channel series Alaskan…

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup?

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup? Nicole Kidman and Keith…

The Last Trapper: “Mountain Men” Star Tom Oar’s Sh0cking Retirement and the Heartbreaking Reason He’s Leaving the Wilderness Behind

In the heart of Montana’s rugged Yaak Valley, where the wild still reigns supreme, a living legend has made a…

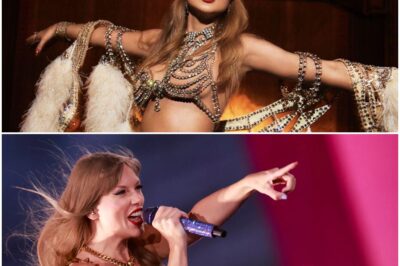

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week Pop superstar Taylor Swift…

End of content

No more pages to load