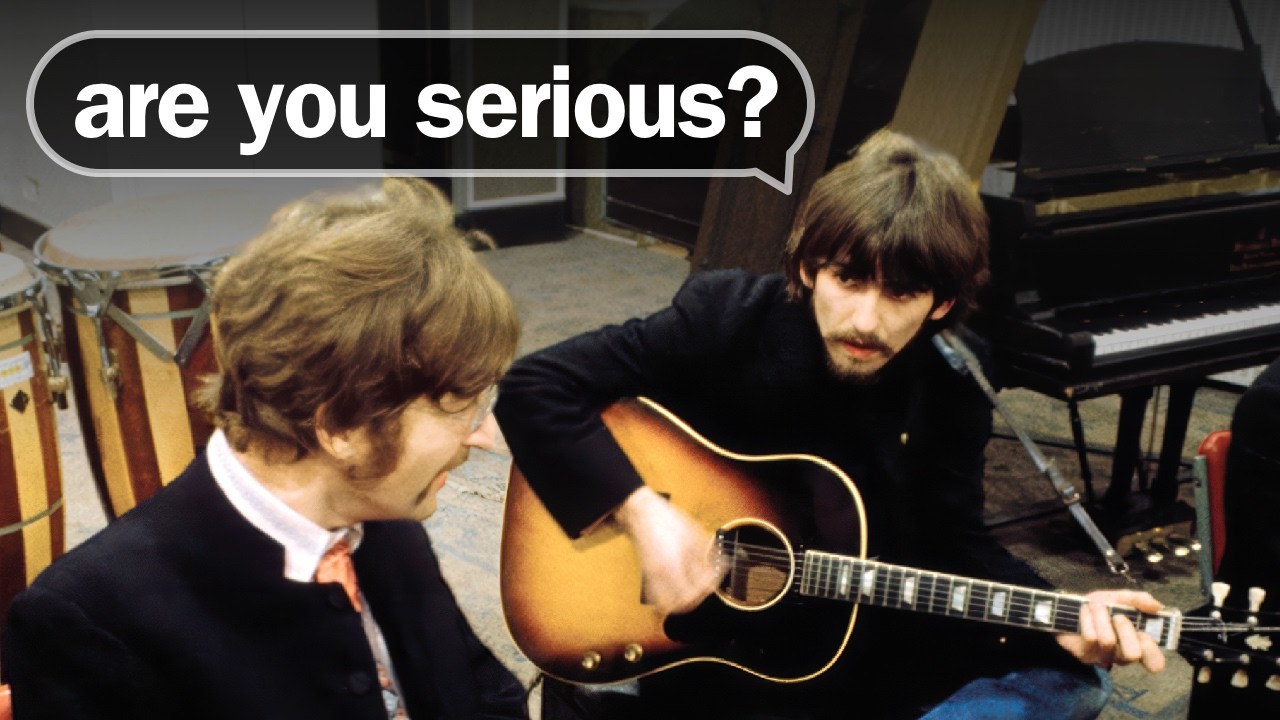

In the sprawling, legendary catalog of The Beatles, there are songs that define eras, inspire generations, and break new creative ground. But only one carries the weight of a technical impossibility overcome by a stroke of pure, unbelievable luck. That song is John Lennon’s ethereal, nostalgic masterpiece, “Strawberry Fields Forever.” It is, as engineer Jeff Emmerick recalls Lennon calling it, “our greatest achievement”, an artifact of sound born from an unprecedented level of studio experimentation and a demand for perfection that pushed producer George Martin and his team to the absolute brink.

The genesis of this revolutionary track lies not just in John Lennon’s introspective genius, but in a pivotal, seismic shift in the band’s career in 1966. After a relentless schedule of touring that had left them exhausted and disillusioned, The Beatles made the radical decision to become solely a studio band. “If we don’t have to tour then we can record music that we won’t ever have to play live,” Lennon rationalized. This single decision was the catalyst for the psychedelic, boundary-shattering music that would follow. With no tour deadlines to meet and no obligation to replicate the music on stage, they were suddenly granted the creative license to “create something that’s never been heard before.”

This new mandate was perfectly captured in a conversation engineer Jeff Emmerick overheard between Lennon and Martin on their first day back in the studio since completing Revolver. Lennon declared, “We’re fed up with making soft music for soft people and we’re fed up with playing for them too… it’s given us a fresh start.” The Beatles were ready to forge a new sonic identity. With this new-found creative hunger, Lennon introduced the group to “Strawberry Fields Forever,” a song Paul McCartney immediately declared “absolutely brilliant.”

The Roots of Nostalgia and a Spanish Retreat

To understand the complexity of the final recording, one must first grasp the deeply personal core of the song. Strawberry Fields Forever is a reflection of John Lennon’s challenging yet cherished early years. Strawberry Field was a Salvation Army children’s home near where he grew up in Liverpool. As a boy, he would play in the gardens, often attending the summer parties where a band would play, taken there by his Aunt Mimi, who raised him due to his parents’ absence. This location became a potent symbol of introspection and sanctuary for Lennon.

Lennon began writing the song in September 1966 while on set for the film How I Won the War in the south of Spain. Separated from the collaborative, fast-paced environment of the Lennon-McCartney songwriting partnership, John had extensive time to develop his new song, beginning to layer in the “beautiful nostalgic tone” that permeates even the bare-bones early demos.

The Tale of Two Takes: Gentle vs. Thunderous

When The Beatles returned to the studio in November 1966, ready to begin work on what would eventually become Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Lennon insisted on starting with his new track.

The first complete performance, Take One, was notably sparse and almost unrecognizable from the final version. It didn’t begin with the iconic chorus but instead with a verse, featuring John on electric guitar, minimal drums, and some simple slide guitar. After refining the structure—notably arranging it to start with the chorus after Paul McCartney introduced the idea of opening with the haunting Mellotron—they eventually settled on a full recording. This version, epitomized by Take Six and Take Seven, was performed in the lower key of B-flat, establishing a tone that was distinctively “gentle.”

It should have been finished. They had a complete, beautifully melancholic take, which was later bounced down and overdubbed with a new lead vocal on Take Seven. But John Lennon, demanding perfection, returned to George Martin with a clear dissatisfaction: “It really wasn’t what I quite what I had in mind when I wrote the song… could we do it again?”

Lennon’s new demand was for a “heavier” style. The second round of recording resulted in a radically different track. For this version, they returned to Lennon’s original key of C major, necessary because, as the video notes, “the lowest note available on the cello is a C.” The tempo was much quicker. This was an orchestral, thunderous sonic assault. Ringo Starr played the drums “as loud as he could,” while Martin arranged strings and brass. The song was layered with a cacophony of sound, including reverse cymbal sounds, George Harrison playing the shimmering Indian Swarmandal harp, and a psychedelic chaos of sound at the end. This version, culminating in Take 26, was energetic, powerful, and complete, perfectly fulfilling the request for a heavier sound.

The Impossible Request: “I’m Sure You Can Fix It”

Once again, the song should have been finished. But just as before, John Lennon returned to George Martin, compounding the complexity. He now liked elements from both versions: “You know I actually like a lot of the old one.” His simple, terrifying request was to take the beginning of the gentle, slower Take Seven and splice it seamlessly with the end of the thunderous, faster Take 26.

The two fundamental problems, as George Martin quickly pointed out, were catastrophic: “They’re in different keys and they’ve got different tempos.” Merging a recording in the key of B-flat with one in C major, at entirely different speeds, was technically “impossible” using the rudimentary, four-track technology of the time. Lennon’s response was the stuff of legend, a testament to his expectation of genius: He looked at Martin, wearing his spectacles, and simply said, “I’m sure you can fix it.”

Faced with this demand, Martin and engineer Jeff Emmerick were forced to attempt the impossible. Their only tools were a reel-to-reel tape machine and a pair of scissors. They had to precisely cut the two tapes and line them up. The solution involved changing the playback speed of one or both tapes to manually align the tempos.

And then, the moment of sheer, astonishing coincidence occurred. As they began to match the tempos of the two different takes, an unforeseen miracle happened: the change in speed required to match the tempo of Take 26 to Take Seven automatically—and perfectly—aligned the pitches to the same key. By slowing down the second, heavier take “just slightly,” the key of C major dropped down to B-flat, making the splice possible. With a precise cut of the tape and a subtle crossfade, the gentle Mellotron opening seamlessly melted into the heavy, crashing drums and orchestral soundscape, creating the final, revolutionary track we know today.

The final track is a perfect hybrid, a fusion of two distinct musical minds and two radically different studio sessions, a testament to John Lennon’s vision and the technical wizardry of George Martin and Jeff Emmerick. The fact that the tempo and key aligned by pure chance when trying to solve one problem is perhaps the most incredible, unrepeatable moment in The Beatles’ storied recording history.

After a month of grueling work, “Strawberry Fields Forever” was finally complete. Although it never made the Sgt. Pepper album—being released as a single along with “Penny Lane”—it confirmed The Beatles’ status as unparalleled sonic pioneers. While other bands saw the four-track studio limitations as a reason for simplicity, The Beatles saw it as “an opportunity to be inventive.” Their willingness to work so hard to achieve a perfect, impossible vision—risking their entire creation on a precise cut—was something no other band of the era could match. “Strawberry Fields Forever” remains a permanent reminder of how genius, audacity, and a touch of fate can converge to change the course of music history.

News

The Tragic Toll on the ‘Pawn Stars’ Family: Inside the Devastating Losses of the Old Man and Rick Harrison’s Son

The Tragic Toll on the ‘Pawn Stars’ Family: Inside the Devastating Losses of the Old Man and Rick Harrison’s Son…

The Double Tragedy That Rocked Pawn Stars: Honoring the Lives of Richard ‘The Old Man’ and Adam Harrison

The World Famous Gold & Silver Pawn Shop on the bustling streets of Las Vegas has been the backdrop for…

The Silent Toll of the Wild: Remembering the 12 Beloved Mountain Men Cast Members Who Tragically Passed Away

The Silent Toll of the Wild: Remembering the 12 Beloved Mountain Men Cast Members Who Tragically Passed Away For…

Beyond the Cameras: Sue Aikens Sues ‘Life Below Zero’ Producers Over Claims of Forced Dangerous Acts and On-Camera Suffering

Beyond the Cameras: Sue Aikens Sues ‘Life Below Zero’ Producers Over Claims of Forced Dangerous Acts and On-Camera Suffering For…

The Unseen Cost of Freedom: Shocking Realities of the Life Below Zero Cast in 2025

The Unseen Cost of Freedom: Shocking Realities of the Life Below Zero Cast in 2025 For over a decade,…

The Silent Toll of the Arctic: Honoring the ‘Life Below Zero’ Stars We’ve Tragically Lost

The Silent Toll of the Arctic: Honoring the ‘Life Below Zero’ Stars We’ve Tragically Lost For over a decade, the…

End of content

No more pages to load