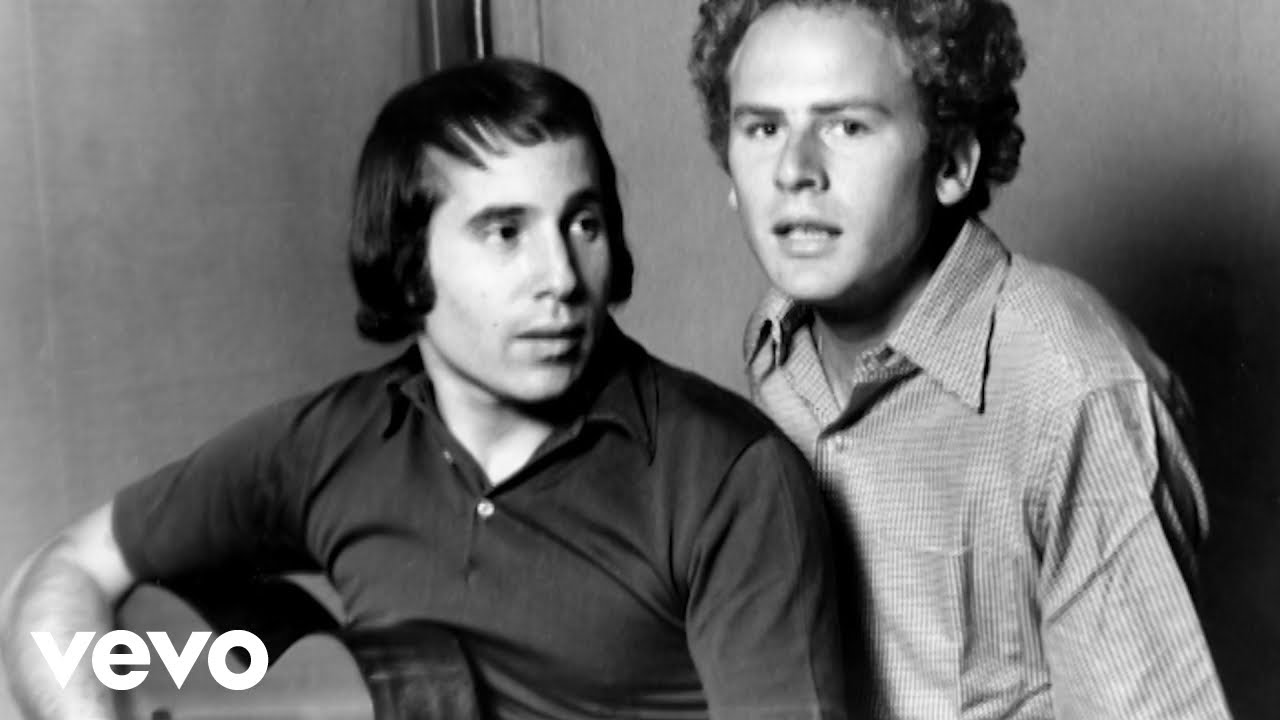

In the annals of music history, few songs have achieved the mythical status of “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” It is more than a song; it’s a hymn for the struggling, a universal anthem of solace and support that has comforted millions in their darkest hours. Its soaring melody and Art Garfunkel’s ethereal, pitch-perfect vocal performance feel like a divine assurance that everything will be alright. Yet, beneath the surface of this musical sanctuary lies a story of profound irony—a tale of friendship, ego, and betrayal. This song, a testament to unwavering support, became the very catalyst that fractured one of the most successful musical duos of all time, Simon & Garfunkel.

The story begins not in a moment of conflict, but one of quiet inspiration. In the summer of 1969, Paul Simon was living in a rented house on Blue Jay Way in Los Angeles, the same house where George Harrison had written “Blue Jay Way.” He found himself listening obsessively to “Oh, Mary, Don’t You Weep,” a gospel track by The Swan Silvertones, featuring the electrifying vocals of Claude Jeter. One line, in particular, grabbed him: “I’ll be a bridge over deep water if you trust in my name.” The phrase resonated deep within Simon’s soul. It was a perfect, crystalline metaphor for support, and it planted a seed.

At the time, Simon felt his partner, Art Garfunkel, was entering a period of profound uncertainty. Garfunkel was in Mexico, filming Mike Nichols’ gritty adaptation of Catch-22. It was a grueling, protracted shoot that left him feeling isolated and adrift, questioning his place in the world and in their musical partnership. Sensing his friend’s anxiety, Simon began to craft a musical lifeline. He envisioned a “little gospel hymn,” a simple, two-verse song meant as a personal gesture of reassurance for Art. It was to be a humble offering, a quiet promise between friends.

“I was thinking of him,” Simon would later recall. “He was in a dark place, and I wanted to tell him I was there for him.” The melody came to him with a fluid, almost spiritual ease, imbued with the gospel and folk traditions he so admired. The lyrics flowed from a place of genuine care: “When you’re weary, feeling small, when tears are in your eyes, I will dry them all.” It was pure, simple, and from the heart. He knew immediately that this was a song for Art to sing. Simon felt his own voice was too limited, too conversational to carry the immense emotional weight the song required. It needed Garfunkel’s voice—that pure, choirboy tenor that could ascend to the heavens.

When Garfunkel returned from filming, Simon presented the song to him. Garfunkel was instantly captivated. He recognized its power, calling it “a monster.” But he also felt a strange sense of hesitation. He initially suggested that Simon should sing it, feeling the sentiment was so intensely personal to its author. But Simon was insistent. “No, it’s for you,” he urged. This small act of creative generosity would have monumental and unforeseen consequences.

As they entered the studio with producer Roy Halee, the “little gospel hymn” began to transform. The song demanded more. It felt incomplete. Simon, a relentless perfectionist, went back to the drawing board and composed a third verse—the powerful, climactic “Sail on, silver girl.” This new section, with its thundering, Phil Spector-esque “Wall of Sound” production, elevated the song from a simple ballad into an epic. Larry Knechtel, a legendary session musician from the Wrecking Crew, was brought in to play the piano. His gospel-inflected performance, which he developed on the spot, became the song’s foundational heartbeat, a perfect blend of reverence and raw emotion.

The recording sessions were arduous and fraught with a new, simmering tension. Garfunkel struggled to nail the vocal. The weight of the song, the sheer perfection it demanded, was immense. He sang it over and over, take after take, from New York to Los Angeles, striving for something transcendent. Roy Halee painstakingly spliced together the best parts of numerous takes to create the final, flawless vocal track that the world would come to know.

While Garfunkel poured his soul into the vocal booth, a subtle but significant power shift was occurring. Paul Simon, the creative engine of the duo, the writer of virtually their entire catalog, was forced into the background. He had written the song, but he was not its voice. Night after night, as Garfunkel delivered his show-stopping performance on tour, audiences would leap to their feet in rapturous, minutes-long standing ovations. Simon would stand to the side, guitar in hand, a spectator to the overwhelming adulation his own creation inspired for another man.

The applause felt like a wedge being driven between them. For Simon, it was a bitter pill to swallow. He had gifted his partner the greatest song he had ever written, only to feel erased by its brilliance. Resentment began to fester. “He came to believe that he was the reason for the applause,” Simon later reflected on Garfunkel’s reception. “And I was the guy standing off to the side.” The song that was meant to be a bridge between them was now exposing the chasm that had been slowly forming for years.

The Bridge Over Troubled Water album became a colossal success, their magnum opus and their swan song. It won six Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year and Song of the Year, and became one of the best-selling albums of all time. But behind the scenes, the partnership was disintegrating. The arguments became more frequent, the creative differences more pronounced. Garfunkel’s burgeoning acting career pulled him away, while Simon felt abandoned, left to carry the musical load alone. The trust and shared ambition that had fueled their rise from teenage friends in Queens to global superstars had evaporated.

The final straw came during the album’s production. The song “Cuba Si, Nixon No” became a point of contention, but the deep-seated issue was the fundamental imbalance that “Bridge Over Troubled Water” had laid bare. The duo officially split in 1970, at the absolute zenith of their fame. The beautiful anthem of friendship ironically served as the eulogy for their own.

In the decades since, the song has lived a life of its own, becoming a cultural touchstone. It has been covered by hundreds of artists, from Aretha Franklin to Elvis Presley, and has served as a source of comfort during times of national tragedy and personal grief. Yet, for the two men who created it, its legacy is forever entwined with pain and regret. It represents both the pinnacle of their collaborative genius and the heartbreaking moment of its dissolution. It is the sound of a promise kept and a bond broken, a beautiful, tragic monument to a friendship that could no longer withstand the weight of its own success.

News

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009”

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009” After over a decade of whispers,…

The Unseen Battle of Matt Brown: The Dark Truth Behind His Disappearance from ‘Alaskan Bush People’

For years, the Brown family, stars of the hit reality series “Alaskan Bush People,” captivated audiences with their seemingly idyllic…

From “Mr. Fixit” to Broken Man: The Unseen Tragedy of Alaskan Bush People’s Noah Brown

Noah Brown, known to millions of fans as the quirky, inventive “Mr. Fixit” of the hit Discovery Channel series Alaskan…

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup?

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup? Nicole Kidman and Keith…

The Last Trapper: “Mountain Men” Star Tom Oar’s Sh0cking Retirement and the Heartbreaking Reason He’s Leaving the Wilderness Behind

In the heart of Montana’s rugged Yaak Valley, where the wild still reigns supreme, a living legend has made a…

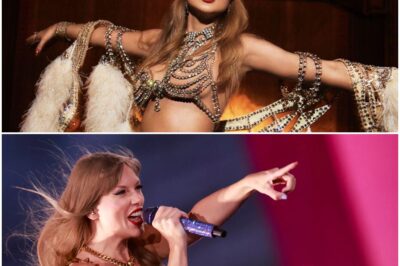

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week Pop superstar Taylor Swift…

End of content

No more pages to load