In the vast and storied catalog of protest music, few songs have ever landed with the force, fury, and tangible consequence of Bob Dylan’s “Hurricane.” Released in 1975, this eight-and-a-half-minute epic was not just a piece of music; it was a battering ram aimed at the walls of the American justice system. It was a furious piece of journalism set to a driving beat, a cinematic narrative that told the world the story of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, a top middleweight boxing contender whose life was derailed by a wrongful conviction for a triple homicide. This is the story of how a song became a crusade, igniting a global movement that ultimately helped to free an innocent man.

Before he was inmate number 45472, Rubin Carter was a force of nature. On the streets of Paterson, New Jersey, and later in the boxing ring, he was known for his explosive power and aggressive, relentless style. He was a folk hero in the making—a man who had overcome a troubled youth to become a world-class athlete on the cusp of a title shot. But Carter was more than just a fighter; he was an outspoken Black man in the racially charged atmosphere of 1960s America, unafraid to speak his mind on civil rights and social injustice. To some, this made him an icon. To others, it made him a target.

On June 17, 1966, that target was painted squarely on his back. Three white people were shot and killed at the Lafayette Bar and Grill in Paterson. Within an hour, Carter and a companion, John Artis, were pulled over by police. The sole surviving victim said neither man was the shooter. They passed lie detector tests. Yet, based on the shaky and later recanted testimony of two career criminals who were trying to get out of their own legal troubles, Carter and Artis were arrested, tried, and convicted by an all-white jury. The prosecution’s case was riddled with inconsistencies and fueled by racial prejudice. Both men were sentenced to three consecutive life terms in prison. The Hurricane was caged.

For nearly a decade, Carter’s story faded into the background, another tragic footnote in a turbulent era. From his cell in Rahway State Prison, he refused to wear a prisoner’s uniform or perform prison labor, steadfastly maintaining his innocence. He poured his rage and intellect into writing his autobiography, “The Sixteenth Round: From Number 1 Contender to #45472,” which was published in 1974. The book was a raw, unfiltered account of his life and the injustice he had suffered. And, by a stroke of fate, a copy of it landed in the hands of Bob Dylan.

Dylan, already a titan of folk and rock music and the voice of a generation, was profoundly moved by Carter’s story of a promising life stolen by a corrupt system. He went to visit Carter in prison, and after meeting the man himself, he was convinced of his innocence. A fire was lit. Dylan channeled his outrage into his art. Collaborating with Jacques Levy, he began to craft a narrative song that would function like a miniature film, laying out the case for the world to see.

The result was “Hurricane.” The song does not begin subtly. It opens with the jarring crack of a snare drum, like a gunshot, and Dylan’s voice, raw and filled with a spitting rage, immediately throws the listener into the scene: “Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night / Enter Patty Valentine from the upper hall / She sees the bartender in a pool of blood / Cries out, ‘My God, they killed them all!’”

From a musical and lyrical standpoint, the song is a masterclass in storytelling. Dylan’s vocal delivery is not melodic; it’s a frantic, desperate, and accusatory sermon. He isn’t just singing; he is testifying. The insistent, almost hypnotic violin played by Scarlet Rivera weaves in and out of the verses, adding a layer of frantic energy and sorrow. The song lays out the entire narrative: the crime, the racial profiling (“In Paterson that’s just the way things go / If you’re Black you might as well not show up on the street / ‘Less you wanna draw the heat”), the flimsy evidence, and the blatant conspiracy to put Carter away. Dylan names names and doesn’t pull a single punch, painting a vivid picture of a man “falsely tried” and turned into a scapegoat.

When “Hurricane” was released as the opening track of the album Desire in late 1975, it was an immediate sensation. It shot up the charts, bringing Rubin Carter’s case from the dusty files of the New Jersey court system onto the global stage. The song was played on radios across the world, and with every listen, more people learned of the injustice. It was impossible to ignore. Dylan didn’t stop there. He organized two benefit concerts, dubbed the “Night of the Hurricane,” featuring some of the biggest names in music, including Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, and Muhammad Ali, who called in his support. The proceeds went to Carter’s legal defense fund.

The song and the subsequent publicity campaign put immense pressure on the state of New Jersey. Celebrities, activists, and ordinary citizens began demanding a new trial. The two key witnesses from the original trial recanted their testimony, admitting they had lied under pressure from the prosecution. In 1976, the New Jersey Supreme Court overturned Carter’s conviction, citing grave errors in the original trial, and ordered a new one. For a moment, it seemed justice was at hand.

However, the system did not give up so easily. In the second trial, the prosecution built a new case, this time arguing that the murders were an act of racial revenge. Despite the lack of credible evidence, Carter was convicted once again. It was a crushing blow, but the movement sparked by Dylan’s song refused to die. The fight for Carter’s freedom continued for another nine long years.

Finally, in 1985, Judge H. Lee Sarokin of the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey overturned the second conviction. In a scathing ruling, he wrote that the prosecution had been “predicated upon an appeal to racism rather than reason, and concealment rather than disclosure.” After nearly two decades behind bars for a crime he did not commit, Rubin “Hurricane” Carter was finally a free man.

So, did a song really change history? In the most direct sense, no single song can single-handedly open a prison door. But “Hurricane” was the catalyst. It was the spark that ignited a wildfire of public outrage. It transformed a forgotten local case into an international symbol of racial injustice. Without Dylan’s powerful anthem reaching millions, it is unlikely the resources, legal talent, and public pressure would have ever been marshaled to fight for Carter’s cause for so long and with such intensity.

The legacy of “Hurricane” is a powerful testament to the role of the artist as an activist. It demonstrates that music can be more than entertainment; it can be a vehicle for truth, a voice for the voiceless, and a powerful tool in the fight for justice. It reminds us that behind the headlines and court documents are human stories, and sometimes, it takes a songwriter’s fury to make the world stop and listen.

News

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009”

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009” After over a decade of whispers,…

The Unseen Battle of Matt Brown: The Dark Truth Behind His Disappearance from ‘Alaskan Bush People’

For years, the Brown family, stars of the hit reality series “Alaskan Bush People,” captivated audiences with their seemingly idyllic…

From “Mr. Fixit” to Broken Man: The Unseen Tragedy of Alaskan Bush People’s Noah Brown

Noah Brown, known to millions of fans as the quirky, inventive “Mr. Fixit” of the hit Discovery Channel series Alaskan…

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup?

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup? Nicole Kidman and Keith…

The Last Trapper: “Mountain Men” Star Tom Oar’s Sh0cking Retirement and the Heartbreaking Reason He’s Leaving the Wilderness Behind

In the heart of Montana’s rugged Yaak Valley, where the wild still reigns supreme, a living legend has made a…

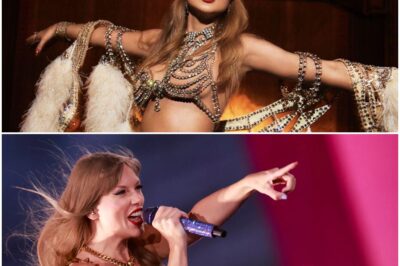

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week Pop superstar Taylor Swift…

End of content

No more pages to load