It wasn’t born in a state-of-the-art recording studio under the meticulous eye of a producer. It didn’t come from a drug-fueled jam session or a deliberate attempt to write a chart-topping hit. Instead, one of the most radiant, optimistic, and universally beloved songs in music history, “Here Comes the Sun,” was born out of an act of rebellion—a quiet, desperate escape from a world that had become cold, gray, and suffocating. For its author, George Harrison, it was more than a song; it was a deep, cleansing breath after nearly drowning.

The year was 1969, and the dream was dying. The Beatles, the four lads from Liverpool who had conquered the world with sound, were now prisoners of their own success. Their empire, Apple Corps, conceived as a utopian creative hub, had devolved into a corporate labyrinth of financial chaos and legal warfare. The London air was thick with an endless, miserable winter, a feeling mirrored in the sterile boardrooms where the band now spent their days. Instead of making music, they were making enemies—of each other.

The arguments were relentless, circling around contracts, managers, and money. Paul McCartney favored his father-in-law, Lee Eastman, to manage their affairs. John Lennon, with Yoko Ono at his side, was fiercely loyal to the abrasive and controversial Allen Klein. Harrison and Ringo Starr were caught in the middle of a power struggle that felt less like a band disagreement and more like a bitter divorce. The camaraderie that had fueled their ascent was gone, replaced by suspicion, resentment, and exhaustion.

On one particularly grim day, Harrison decided he’d had enough. He looked around the room at the scowling faces, the endless stacks of paper, the joyless reality of what being a Beatle had become, and he simply walked out. “It was just a really crappy time,” he would later reflect. He decided to play hooky, ditching the soul-crushing business meeting for the sanctity of a friend’s home. That friend was Eric Clapton.

Driving out to Clapton’s country house in Surrey, Harrison could feel the weight lifting with every mile. He stepped out into the sprawling, sun-drenched garden, a stark contrast to the gloom he had just left behind. Clapton handed him an acoustic guitar, and as Harrison strolled through the greenery, feeling the first real warmth of spring on his skin, the song simply arrived. It wasn’t forced or agonized over. It was a gift, an emotional release that poured out of him fully formed.

“Little darlin’, it’s been a long, cold, lonely winter…”

The opening lines were a literal reflection of the miserable English weather, but they carried the full metaphorical weight of his recent life. The “ice slowly melting” wasn’t just on the ground; it was the thawing of his own spirit. The song was a pure, unadulterated expression of relief. The chords, bright and cascading, felt like sunlight itself. In that moment, Harrison wasn’t the “quiet Beatle” overshadowed by the Lennon-McCartney songwriting machine. He was a man finding his own voice, celebrating a simple, profound moment of peace.

When Harrison brought his sun-drenched anthem back to the band, the atmosphere at Abbey Road Studios was still thick with tension. The Beatles were in the process of recording their final masterpiece, Abbey Road, a project that felt like a last-ditch effort to prove they could still create magic together, even as they were personally falling apart. Yet, the undeniable beauty and optimism of “Here Comes the Sun” were infectious.

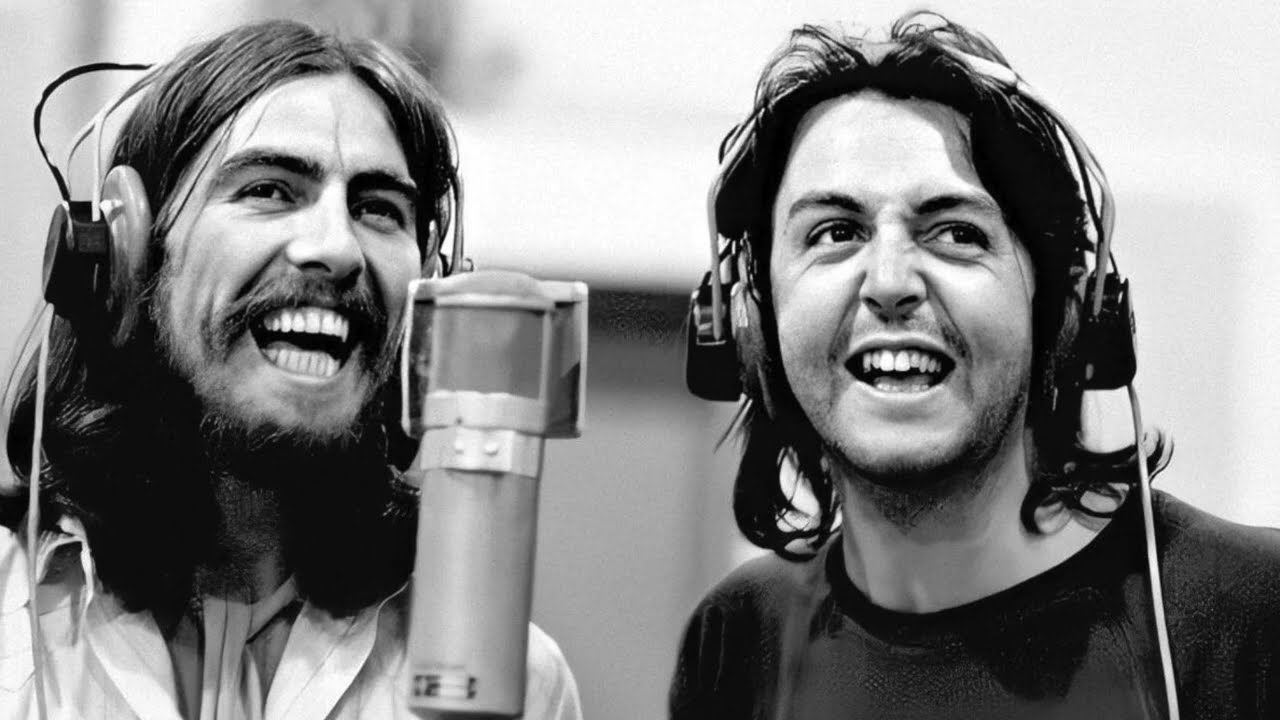

The recording sessions for the song began on July 7, 1969, which happened to be Ringo Starr’s 29th birthday. But there was a conspicuous absence. John Lennon was nowhere to be seen. Just days earlier, he and Yoko Ono had been in a serious car crash in Scotland, and he was hospitalized. Even after his recovery, he never contributed to the track. While his accident provided the official reason, many close to the band felt it was also symbolic. Lennon was emotionally and creatively detaching, his focus consumed by his relationship with Ono and his burgeoning solo career. His absence makes “Here Comes the Sun” one of the very few Beatles tracks recorded by just three members: Harrison, McCartney, and Starr.

This trio, however, poured their collective genius into the song. The basic track was laid down with Harrison on his Gibson J-200 acoustic guitar (borrowed from Clapton), McCartney on bass, and Starr on drums. They captured the song’s gentle, rolling rhythm in 13 takes. From the very beginning, Harrison had a grand vision for the track, one that went beyond a simple acoustic folk song. He heard an orchestra. He heard complex harmonies. And he heard something new and futuristic.

One of the defining elements of the song is the ethereal, watery synth line that floats through the bridge. This was created on a brand new, monstrously large Moog synthesizer, which Harrison had recently purchased and brought into the studio. At the time, the instrument was a rare and complex piece of technology, and Harrison was one of the first musicians in England to own one. He painstakingly layered the Moog’s ribbon controller to create that otherworldly sound, a touch of cosmic wonder that elevates the track from a simple folk tune to a sophisticated piece of pop art.

Over the following weeks, the song was meticulously built, layer by layer. On August 4th, McCartney and Harrison spent the entire day recording their iconic backing vocals. Their harmonies, perfectly intertwined, became the sound of angels heralding the dawn. Harrison then added electric guitar, run through a Leslie speaker to give it a shimmering, liquid quality.

The final, majestic touch came on August 15th, when producer George Martin brought in an orchestra of 17 musicians to add strings, flutes, clarinets, and other woodwinds. Martin’s arrangement is a masterclass in subtlety, swelling and receding to support Harrison’s melody without ever overpowering it. It was the sound Harrison had imagined in Clapton’s garden, fully realized. He even went back a few days later to add one final part: a lost guitar solo. For decades, fans were unaware that a stunning, intricate solo had been recorded but ultimately cut from the final mix. It was only rediscovered years later, a hidden gem that revealed even more of the song’s quiet brilliance.

“Here Comes the Sun” became the radiant heart of Abbey Road. Placed as the opening track of side two, it was a burst of pure light after the darker, heavier sounds that preceded it. It was George Harrison’s ultimate triumph. For years, he had struggled to get his songs onto Beatles albums, often limited to one or two tracks per record. With Abbey Road, he delivered not one, but two of the album’s strongest and most enduring songs: “Here Comes the Sun” and “Something.” He had finally stepped out from the shadows and proven himself an equal to his more famous bandmates.

Tragically, the hope embodied in the song was fleeting for the band itself. The brief unity found in creating Abbey Road could not mend the deep fractures. The album was their swan song, a final, magnificent statement before they dissolved into acrimony and lawsuits. “Here Comes the Sun” was not the dawn of a new era for The Beatles, but rather a beautiful sunset.

Yet, the song’s legacy is one of enduring hope. It has transcended its origins to become a global anthem for optimism, a go-to track for graduations, weddings, and the first sunny day of spring. It’s a testament to the power of a single moment of clarity and escape—a reminder that even in the longest, coldest, and loneliest of winters, the sun will, eventually, return. It is the sound of one man finding his freedom, and in doing so, giving the world a timeless gift.

News

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009”

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009” After over a decade of whispers,…

The Unseen Battle of Matt Brown: The Dark Truth Behind His Disappearance from ‘Alaskan Bush People’

For years, the Brown family, stars of the hit reality series “Alaskan Bush People,” captivated audiences with their seemingly idyllic…

From “Mr. Fixit” to Broken Man: The Unseen Tragedy of Alaskan Bush People’s Noah Brown

Noah Brown, known to millions of fans as the quirky, inventive “Mr. Fixit” of the hit Discovery Channel series Alaskan…

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup?

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup? Nicole Kidman and Keith…

The Last Trapper: “Mountain Men” Star Tom Oar’s Sh0cking Retirement and the Heartbreaking Reason He’s Leaving the Wilderness Behind

In the heart of Montana’s rugged Yaak Valley, where the wild still reigns supreme, a living legend has made a…

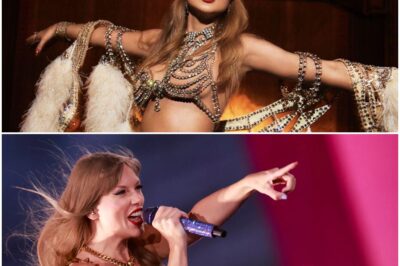

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week Pop superstar Taylor Swift…

End of content

No more pages to load