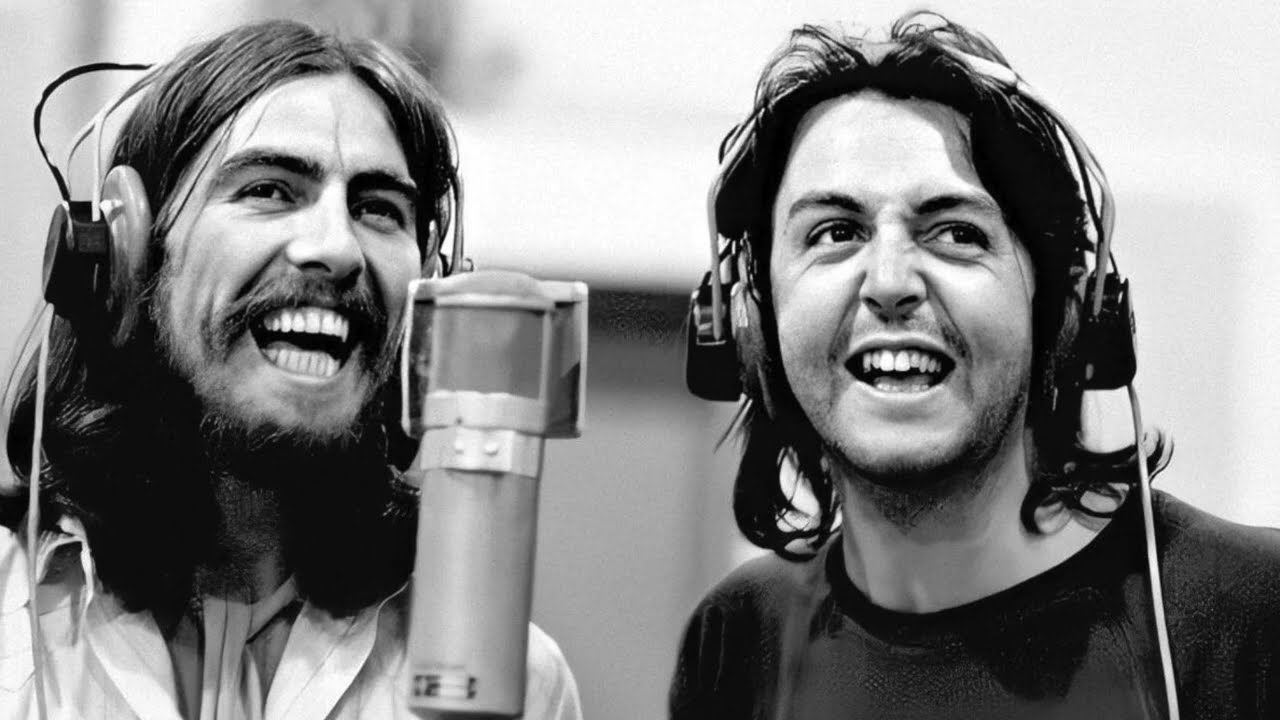

The Ultimate Studio Secrets of ‘Here Comes the Sun’: The Day George Harrison Erased an Orchestra and The Beatles Said Goodbye

Few songs in the vast, transcendent catalogue of The Beatles possess the immediate, universally recognized warmth and simple joy of “Here Comes the Sun.” It is a track that has effortlessly transcended generations, serving not only as one of the band’s most treasured works but, perhaps ironically, as the modern “Gateway” for millions of new fans, reigning today as the most-streamed Beatles song across the globe. Yet, beneath its bright, effervescent surface lies a complex, at times baffling, recording history—a mosaic of production anomalies, lost solos, a musical mystery, and the poignant fact that its final mixing session coincided with the final time the four members of the band would ever be together in the studio.

This three-minute masterpiece, appearing on the second half of the band’s iconic 1969 farewell album, Abbey Road, stands apart for a crucial reason: it was penned not by the titanic duo of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, but by the quartet’s youngest member, George Harrison. For years, Harrison had labored in the formidable shadow of Lennon-McCartney, his genius often relegated to one or two slots per album. But with “Here Comes the Sun,” alongside its magnificent album counterpart, “Something,” Harrison unequivocally declared his arrival as a songwriting force, capable of producing compositions of timeless emotional resonance.

The Writer’s Rebellion in the Garden

The genesis of the song is as idyllic as its resulting sound. By 1969, the business affairs of The Beatles were spiraling into a vortex of financial and legal acrimony, making studio time as stressful as it was creative. According to Harrison’s later accounts, the song was conceived as an act of rebellion and sanctuary. He deliberately skipped a particularly grueling business meeting at the Apple Corps headquarters. Seeking refuge and solace, he drove to the English countryside estate of his friend, guitar legend Eric Clapton.

There, on a beautiful early spring day, with the sun finally breaking through the clouds after what felt like a long, hard winter, Harrison picked up one of Clapton’s acoustic guitars. The bliss of the moment—the sheer relief of freedom from the oppressive business pressures—translated directly into the song’s central, hopeful theme. It wasn’t a forced composition; it was an organic, deeply personal expression of optimism. The resulting tune, with its unforgettable melody and uplifting message, captured a fleeting moment of peace that Harrison desperately needed.

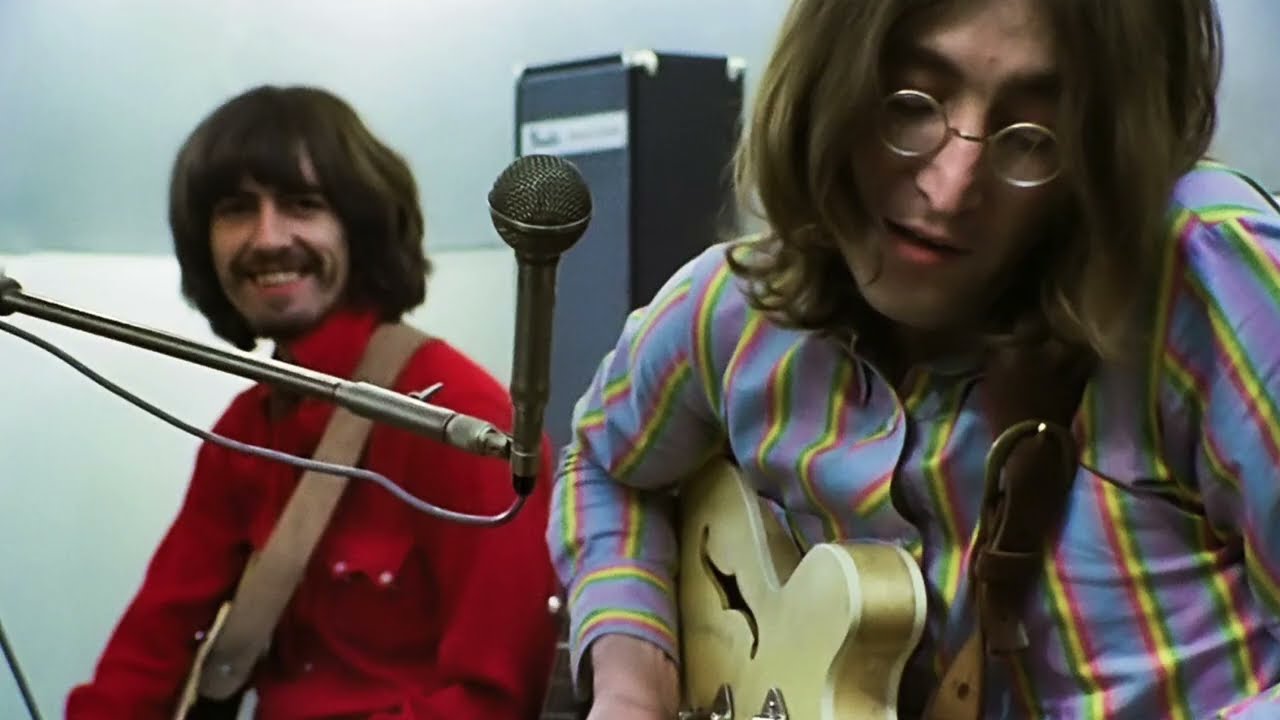

The Fab Three and a Vanishing Act

The formal recording sessions for Abbey Road began in the summer of 1969. Work on “Here Comes the Sun” started on July 7th. The basic rhythm track was meticulously captured over thirteen takes, with a notable absence: John Lennon was not present, recovering from a recent car accident in Scotland. This meant that the core track was laid down by George Harrison on acoustic guitar, Paul McCartney contributing a typically elegant and intricate bass line, and Ringo Starr delivering one of the most dazzling and subtle drum performances of his career.

From this basic foundation, Harrison began layering his textures. After recording his lead vocal, he partnered with Paul McCartney for the gorgeous, double-tracked harmony vocals, lending the song its signature vocal warmth. But Harrison, ever the sonic explorer, was just beginning.

One of the first major production quirks involved Harrison’s electric guitar work. On certain surviving parts, he chose not to play through a standard amplifier. Instead, he channeled his guitar through a Leslie speaker—a specialized speaker with a rotating chamber most famously used with a Hammond organ to create a swirling, ethereal sound. The effect transformed the guitar’s tone into something almost unrecognizable and otherworldly. Harrison was so taken with the sound that he noted on the lyrics sheet that this part was the “son of badge,” a playful reference to the song “Badge” he had co-written with Eric Clapton, where he first experimented with the Leslie effect on guitar.

Intriguingly, the mid-August sessions also saw Harrison record a full electric guitar solo, a vibrant addition that was later rediscovered during a 2011 documentary about his life. Ultimately, Harrison, ever the perfectionist, felt the solo didn’t quite fit the song’s overall aesthetic and instructed the EMI engineers to omit it from the final mix. This act highlights a crucial tension in the track’s development: balancing Harrison’s urge to experiment with his desire for purity and simplicity.

The Moog, the Mix, and the Mistake

George Martin, the band’s long-time producer, contributed a beautiful, lush orchestral arrangement for a string and woodwind ensemble, which was recorded on August 15th. For most artists, this would have been the final, polishing touch. But Harrison had one last, powerful ingredient he wanted to add: the Moog modular synthesizer.

George Harrison was one of the earliest adopters of this groundbreaking electronic instrument in the UK, having commissioned a custom-built unit after first witnessing its capabilities while producing another artist in Los Angeles. He was so enchanted by its otherworldly, futuristic sounds that he even released an experimental album, Electronic Sound, using it. For the Abbey Road sessions, the heavy, complex machine had to be transported from his home to EMI Studios by road manager Mal Evans. Though Harrison reportedly received minimal guidance on its operation, his “tinkering” on the Moog was, in a word, sublime, producing the celestial whooshes and waves of sound that permeate “Here Comes the Sun” (and also appear on tracks like “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and “Because”).

Here is where the major production anomaly—the great studio mishap—occurred. According to the detailed notes from the Abbey Road Super Deluxe Edition, when Harrison recorded the Moog part, he did so onto the exact same track that already contained George Martin’s freshly recorded woodwind overdub. In the days before infinite digital tracks, this was effectively an act of erasure. The Moog overdub replaced the woodwinds entirely.

Or, rather, almost entirely.

The tape’s timing meant that one tiny section of the original woodwinds survived and can be heard briefly after the bridge, precisely when the Moog is silent. Harrison’s bold electronic experimentation effectively wiped out a carefully crafted piece of orchestral work, leaving behind a subtle, accidental ghost of music that is still audible today—a testament to the chaotic, often high-stakes, process of late-era Beatles recording.

The Final Day and a Lingering Mystery

As if the technical quirks weren’t enough, the song carries profound emotional weight linked to The Beatles’ final moments. When the beautifully layered, packed eight-track tape was finally ready for mixing, the date was August 20, 1969. This specific date is significant for one deeply bittersweet reason: it marked the last time that all four Beatles—Paul, John, George, and Ringo—were ever together in the studio. They were nearing the end of their unparalleled seven-year creative journey in the hallowed halls of EMI.

One of their last collective tasks that day was to determine the final order of songs for the album. Their decision to place “Here Comes the Sun” as the opener to the album’s second half was brilliant. It follows the immense, abrasive intensity of John Lennon’s “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” which ends abruptly on a swelling wave of multi-track guitars and electronic noise. The sudden silence, followed by the gentle, optimistic opening of “Here Comes the Sun,” provides a breathtaking, immediate reset—a perfect transition from darkness into light, leading listeners into the final, joyful Abbey Road medley.

Finally, the song is entangled in a curious, unsolved musical mystery involving John Lennon. A subtle coincidence exists in the sequencing, as both sides of Abbey Road happen to open with the same two words. However, three songs into the medley, John Lennon’s “Sun King” also opens with the very similar phrase “Here comes the sun.” This has sparked debate: Did Lennon’s early, unreleased tape recordings of a riff inspire George? Or did Lennon deliberately write his lyrics as a cheeky callback to George’s finished song, perhaps referencing the historical “Sun King,” Louis XIV, through wordplay?

Neither Lennon nor Harrison ever spoke publicly about this uncanny lyrical connection, adding to the intrigue. Given that Sun King was recorded a few weeks after George’s composition was well underway, the prevailing and more plausible theory is that Lennon’s lyrics were a conscious, affectionate nod to George, a final, unspoken moment of collaborative spirit in the twilight of the band’s life.

The Timeless Power of Optimism

Decades after its complex creation, the impact of “Here Comes the Sun” cannot be overstated. Along with “Something,” it validated George Harrison’s position as a songwriter, silencing any early, harsh critics who had dismissed his contributions to Abbey Road as “mediocrity incarnate.” Time has proven those critiques laughably wrong. Harrison’s talent would be fully confirmed the following year with his monumental triple album, All Things Must Pass.

Harrison continued to perform his anthem of optimism throughout his career, including a memorable 1971 performance at the Concert for Bangladesh and an intimate, gorgeous duet with Paul Simon on Saturday Night Live in 1976. Despite the internal chaos, the forgotten solos, the electronic accidents, and the bittersweet farewell of its recording, the core message of the song endures. Harrison wrote the track during a harrowing, high-pressure period, yet it resulted in a universal testament to resilience. No matter how long the cold, dark winter of our lives may seem, the sun will always return, and “it’s all right.” This simple, profound truth is why “Here Comes the Sun” remains not just a classic, but The Beatles’ most enduring digital success story.

News

The Tragic Toll on the ‘Pawn Stars’ Family: Inside the Devastating Losses of the Old Man and Rick Harrison’s Son

The Tragic Toll on the ‘Pawn Stars’ Family: Inside the Devastating Losses of the Old Man and Rick Harrison’s Son…

The Double Tragedy That Rocked Pawn Stars: Honoring the Lives of Richard ‘The Old Man’ and Adam Harrison

The World Famous Gold & Silver Pawn Shop on the bustling streets of Las Vegas has been the backdrop for…

The Silent Toll of the Wild: Remembering the 12 Beloved Mountain Men Cast Members Who Tragically Passed Away

The Silent Toll of the Wild: Remembering the 12 Beloved Mountain Men Cast Members Who Tragically Passed Away For…

Beyond the Cameras: Sue Aikens Sues ‘Life Below Zero’ Producers Over Claims of Forced Dangerous Acts and On-Camera Suffering

Beyond the Cameras: Sue Aikens Sues ‘Life Below Zero’ Producers Over Claims of Forced Dangerous Acts and On-Camera Suffering For…

The Unseen Cost of Freedom: Shocking Realities of the Life Below Zero Cast in 2025

The Unseen Cost of Freedom: Shocking Realities of the Life Below Zero Cast in 2025 For over a decade,…

The Silent Toll of the Arctic: Honoring the ‘Life Below Zero’ Stars We’ve Tragically Lost

The Silent Toll of the Arctic: Honoring the ‘Life Below Zero’ Stars We’ve Tragically Lost For over a decade, the…

End of content

No more pages to load