In the spring of 1966, inside the hallowed walls of EMI’s Abbey Road Studio Two, a 25-year-old John Lennon approached his esteemed producer, George Martin, with a request that teetered between the impossible and the insane. “I want my voice to sound like the Dalai Lama chanting from the top of a mountain,” he explained, deadpan. For any other artist, it would have been dismissed as a joke. But this was The Beatles, a band that had conquered the world and was now profoundly bored with its limitations. This one surreal request would trigger a sonic revolution, culminating in “Tomorrow Never Knows,” a song that didn’t just break the rules of pop music—it vaporized them.

The Beatles were at a crossroads. They were the most famous people on the planet, but the deafening screams of Beatlemania had rendered their live performances musically pointless. Trapped in a gilded cage of touring and formulaic pop hits, they were desperate for a new direction. The answer arrived not in a melody, but in a mind-altering chemical: LSD. Lennon, in particular, had embraced the psychedelic experience, finding it a gateway to spiritual and creative liberation. His guide was Timothy Leary’s “The Psychedelic Experience,” a manual for navigating acid trips that was itself a reinterpretation of the “Tibetan Book of the Dead.”

Lying on his sofa at his Weybridge home, Lennon would read Leary’s instructions aloud into a tape recorder while tripping: “Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream… It is not dying… Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void…” These phrases, lifted almost verbatim, became the lyrical bedrock of his new song, initially titled “The Void.” It was more than a song; it was a mantra, an attempt to bottle the chaotic, terrifying, and enlightening essence of an acid trip and broadcast it to the world through a three-minute pop record. The challenge was that the technology to do so simply didn’t exist.

Enter George Martin and a 20-year-old recording engineer named Geoff Emerick. Martin, the classically trained producer, was the band’s musical anchor, but even he was baffled by Lennon’s vision. How do you make a voice sound like a distant, ethereal monk? Lennon’s first suggestion was to be suspended from the studio ceiling by a rope, swinging in a circle around a microphone as he sang. While visually dramatic, it was wildly impractical.

The solution came from Emerick’s youthful, rule-breaking ingenuity. He recalled seeing a strange, rotating speaker cabinet in the studio called a Leslie speaker, a device normally used to give the Hammond organ its signature shimmering, Doppler effect. In a moment of pure inspiration that violated EMI’s strict technical protocols, Emerick decided to rewire the console and route Lennon’s vocal track through the Leslie. The result was instantaneous magic. Lennon’s voice was no longer just a voice; it was a swirling, disembodied, ethereal presence. It floated, spun, and echoed as if transmitted from another plane of existence. They had found the Dalai Lama on the mountaintop.

But the psychedelic soundscape was just getting started. Paul McCartney, increasingly influenced by the avant-garde electronic compositions of Karlheinz Stockhausen, had been experimenting at home with tape loops. He would record random sounds—a distorted guitar chord, a wine glass ringing, himself laughing—and then snip the tape and loop it back on itself to create a repeating, rhythmic pattern. Fascinated, the other Beatles followed suit, creating their own chaotic sound collages.

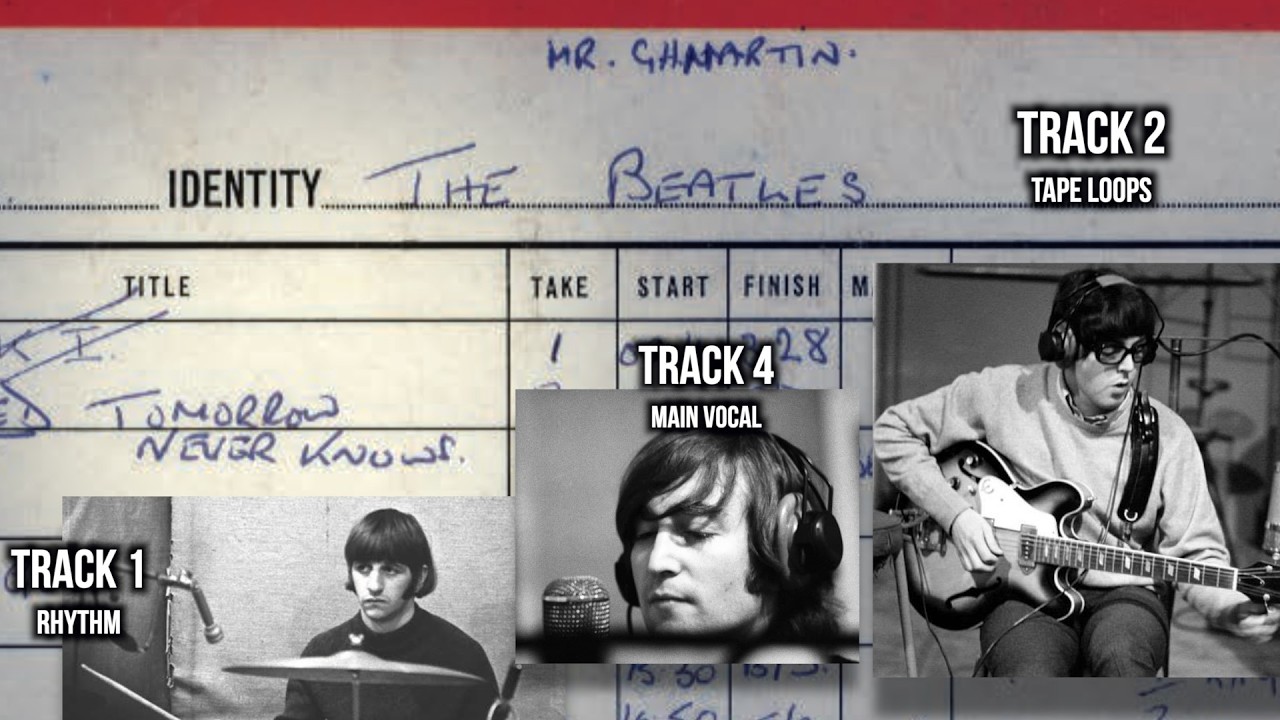

On April 7, 1966, they brought these loops into the studio for what would become one of the most unorthodox recording sessions in history. The scene was one of controlled chaos. Each of the five tape loops was threaded onto a separate tape machine, with the tape snaking out of the machine, around the studio, and back in. To keep the delicate loops from tangling, studio technicians, roadies, and even the other Beatles were enlisted to hold them taut with pencils. George Martin stood at the mixing desk like a mad conductor, raising and lowering faders to fade the cacophony of sounds in and out of the mix at random.

The sounds themselves were alien. McCartney had created a sped-up recording of his own laughter that sounded like a flock of seagulls. There was a B-flat major orchestral chord, a sitar phrase played and then reversed, and other electronic squawks and burbles. Faded in and out over Ringo Starr’s powerful, monolithic drum pattern and a single, hypnotic C-major chord drone played on a tambura, the loops created a sonic collage that was utterly unprecedented. It was the sound of a mind simultaneously fracturing and expanding.

The track was a tapestry of innovation. Ringo’s drumming, often cited as one of his finest performances, was given a revolutionary new sound. Emerick, wanting a bigger, fatter beat, broke another EMI rule by placing a microphone just inches from the bass drum’s skin and then running the signal through a Fairchild limiter, compressing it to the point of distortion. The result was a drum beat that punched through the speakers with a weight and power never before heard on a pop record. To complete the track, George Harrison’s Indian musical influences provided the hypnotic drone, while a guitar solo, originally recorded for the song “Taxman,” was chopped up, reversed, and flown in, adding another layer of disorienting, backward reality.

When the needle dropped on the final track of their new album, Revolver, in August 1966, listeners were stunned. After a suite of brilliant but recognizable pop songs, “Tomorrow Never Knows” was an electrifying shock to the system. It was terrifying, exhilarating, and utterly alien. There were no precedents. It was a broadcast from a future no one knew was coming.

The song marked the definitive end of The Beatles as a touring entity and their rebirth as a purely studio-based band. They had discovered that the recording studio wasn’t just a place to document a performance; it was an instrument in its own right, a laboratory for limitless sonic alchemy. “Tomorrow Never Knows” was the blueprint for psychedelic rock, a direct ancestor to electronic music, and the spiritual godfather of everything from acid house to trip-hop. It opened a Pandora’s box of creative possibilities, proving that a song could be built from textures, noise, and pure imagination. It was the sound of four musicians turning their backs on the world they had created, turning off their minds, and floating downstream into uncharted territory, taking the rest of us with them.

News

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009”

Dan and Phil Finally Confirm Their 15-Year Relationship: “Yes, We’ve Been Together Since 2009” After over a decade of whispers,…

The Unseen Battle of Matt Brown: The Dark Truth Behind His Disappearance from ‘Alaskan Bush People’

For years, the Brown family, stars of the hit reality series “Alaskan Bush People,” captivated audiences with their seemingly idyllic…

From “Mr. Fixit” to Broken Man: The Unseen Tragedy of Alaskan Bush People’s Noah Brown

Noah Brown, known to millions of fans as the quirky, inventive “Mr. Fixit” of the hit Discovery Channel series Alaskan…

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup?

Nicole Kidman & Keith Urban’s Alleged “Open Marriage” Drama: Did Guitarist Maggie Baugh Spark Their Breakup? Nicole Kidman and Keith…

The Last Trapper: “Mountain Men” Star Tom Oar’s Sh0cking Retirement and the Heartbreaking Reason He’s Leaving the Wilderness Behind

In the heart of Montana’s rugged Yaak Valley, where the wild still reigns supreme, a living legend has made a…

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week

Taylor Swift Breaks Another Historic Record With ‘Showgirl’ — Selling 4 Million Albums in One Week Pop superstar Taylor Swift…

End of content

No more pages to load